For almost as long as there have been universities, there have been student-led protests about perceived injustices.

In the Middle Ages, university students like those at Oxford were protected by the Catholic church and became embroiled in violent confrontations with citizens of adjacent towns who resented the students’ privileges and belief that local laws did not apply to them. In 1209, the death of a woman triggered a fight between students and locals that led to the lynching of two students.

While student protests in the 1960s and early 1970s over apartheid in South Africa, charges about heavy-handed government in France under Charles de Gaulle, African American civil rights, and the expansion of the Vietnam War by the United States were also marked by violent confrontations, most student strikes or protests have been more peaceful.

JOHN WOODS / THE CANADIAN PRESS FILES Pro-Palestinian protesters on The Quad at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg on May 8.

That certainly has been the case at the University of Manitoba over the past 90 years. Many student protests were concerned with financial issues, perceived unfairness, and questionable decisions by the university administration, as well as larger world events.

In November 1934, U of M students protested what they argued were high streetcar fares set by the Winnipeg Electric Co. (that then operated the city’s transit system) for transportation to the Fort Garry campus.

In the mid-1940s, students demanded more adequate facilities at the U of M’s old Broadway campus (closed in 1950, it was located on the site of Memorial Park).

Two decades later, 1,200 students boycotted classes and demonstrated at the Legislative Building, protesting an expected rise in student tuition fees. They asked Dr. George Johnson, then the education minister in Progressive Conservative Duff Roblin’s government (who later served as Manitoba lieutenant governor from December 1986 to March 1993), to freeze tuition. As the Free Press reported, he said “no.”

In November 1971, students demonstrated in front of the U.S. Consulate in Winnipeg, then located on Donald Street, to protest the U.S. President Richard Nixon’s approval of an underground nuclear test on Amchitka in the Aleutian Islands off the coast of Alaska.

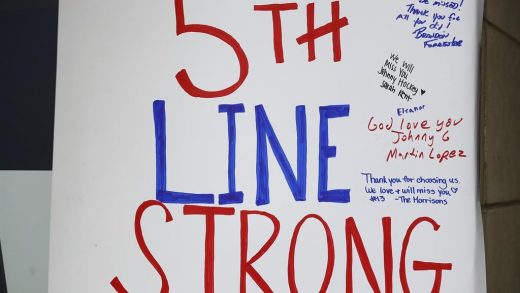

Today, this tradition of protests continues with the student encampment at the U of M (as well as at the University of Winnipeg). Like at numerous university campuses in the U.S and Canada during the past few months, since early May, dozens of students, led by the group Students for Justice in Palestine, have set up tents and erected signs demanding a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza. It is their right to do so and university authorities, whatever their reservations, have not interfered with this lawful freedom of expression and assembly.

Despite the long and complex history of the Middle East, however, the protesters, by their statements and actions tend to see the war in black-and-white terms: Israel is the sole aggressor allegedly guilty of committing genocide, the definition of which in my view (and that of others including U.S. President Joe Biden) has been distorted. There is little, if no, consideration to Hamas’s culpability in this battle; the horrific atrocities and sexual violence Hamas committed last Oct. 7 when its fighters brutally attacked Israeli citizens; the fate of the remaining Israeli hostages being held by Hamas; and Hamas leaders’ utter disregard for the fate of their own people in Gaza.

At the same time, there is much to criticize of the manner in which Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his right-wing coalition have waged this war. Their stated goal of permanently eliminating Hamas seems highly improbable, even if Netanyahu argues this is the only way to protect Israel’s long-term security. And it is hard to know if Netanyahu —who has thus far rebuffed the weekly protests of thousands of Israelis who demand that he end the war so that the remaining hostages can be freed — is instead simply appeasing his right-wing supporters and clinging to power.

Beyond the students’ call for a ceasefire, they have also demanded, among other things, according to a CBC report of May 7, that the university “divest from any companies involved in genocide or discrimination against Palestinians … (join) the global academic boycott of ‘Israeli institutions implicated in human rights violations’; (suspend) exchange programs with Israeli academic institutions; and … (discontinue) a course called ‘Arab Israeli Conflict,’ which the group says perpetuates a biased narrative.” The students have said they will not end their protest until their demands are met.

But just as Dr. Johnson refused student demands about tuition increases in 1965, it is unlikely that university administrators will comply with these demands any time soon. Suffice it to say, that whether they do so or not — and determining a particular company’s investments in “genocide or discrimination against Palestinians” is a difficult, if not an impossible calculation — and will not alter the situation in Gaza or impact Israel in any way.

Moreover, if universities exist in order to facilitate the development of knowledge, critical thinking skills, and advocacy abilities, how is calling for the cancellation of a course and programs intended to broaden students’ perspectives is in keeping with the advancement of academic freedom? The answer is it does not.

Now & Then is a column in which historian Allan Levine puts the events of today in a historical context.