Whether it’s moving vans, food delivery services or everyday drivers, vehicles stopping in bike lanes isn’t an uncommon sight in Winnipeg.

While it is illegal — and subject to a $70 fine — city data shows it isn’t always being ticketed.

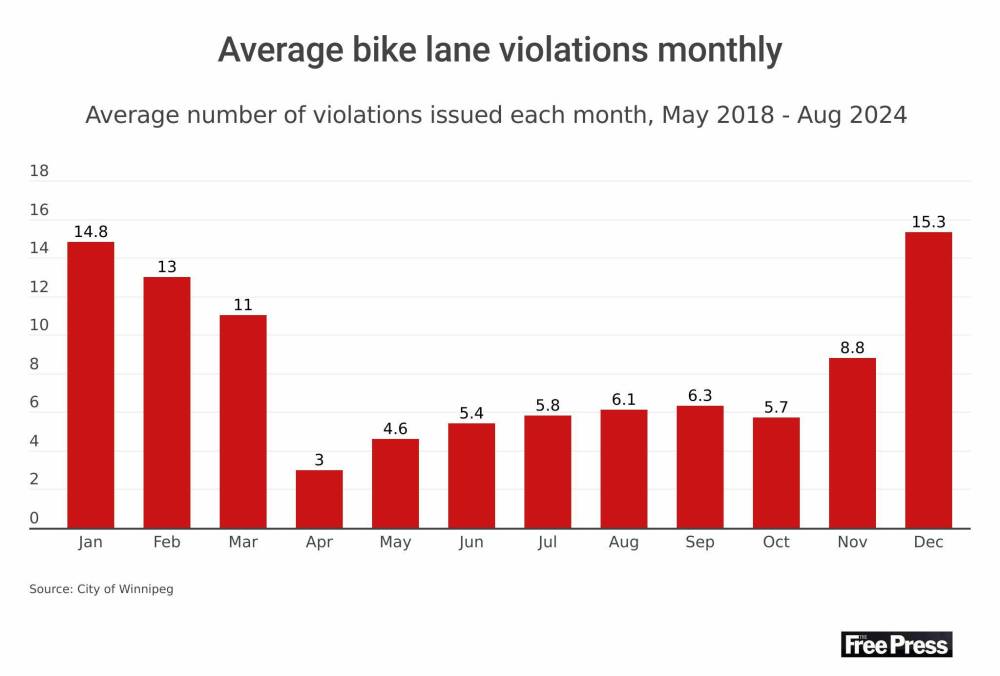

There were 70 tickets handed out between January and August. Most of those tickets (43) were given out in January and February while the other months saw fewer than 10 tickets handed out. There was a single ticket for parking in a bike lane given out in May. Similarly, in 2023, there were fewer than 10 tickets sent out monthly from April to October.

Andrew Kohan, a father of two who describes himself as a “utility cyclist” who uses his bike to transport him and his family as much as possible, says those numbers don’t match the reality on Winnipeg roads.

Andrew Kohan in the bike lane along Assiniboine Avenue (near where a moving vehicle recently blocked the route) on Wednesday. While parking in bike lanes is illegal, it isn’t often ticketed.

“I see people parked in unprotected bike lanes all the time, often with their hazards on, treating it like it’s just a place you can stop, and in the protected bike lanes as well — if it’s a wide enough lane, people will fit their car in it, and will get upset with you if you mention to them that that’s not a place to park,” he said.

“It’s incredibly frustrating to hear that the city isn’t prioritizing enforcement of parking bylaws in bike lanes, because it’s so dangerous when a car is blocking that space.”

He’d like to see proactive bike infrastructure that would make it harder for drivers to circumvent the rules.

“For me, it’s a family safety issue, it’s a life-and-death issue, potentially, and I don’t want to be in that position where I’m forced out of that small amount of safe infrastructure we have,” he said.

This year, most tickets have been handed out on Bannatyne Avenue, Notre Dame Avenue and Arthur Street.

While parking in a bike lane has been a bylaw offence since 2016, the city’s bike infrastructure was integrated into the Winnipeg Parking Authority’s enforcement mapping system to include them in regular officer patrols in late 2023, after a “peak in non-compliance” and a spike in complaints, said Lisa Vermette, the authority’s manager of regulation and compliance.

The parking authority also moved away from issuing tickets through the mail, and instead focused on handing out tickets — and tow orders, which she said were included with every ticket handed out in 2024 — on site.

“Compliance rates are sometimes a very tricky thing to measure,” she said. “The ticket data tells one side of that story.”

Vermette said she hopes compliance is increasing — data over the past few years shows more tickets were handed out in winter months (25 tickets were given out in January 2024, compared to seven in March), which may mean drivers are unknowingly stopping in bike lanes without curbs and avoiding them in other months.

What has decreased, she said, are complaints to 311 about cars in bike lanes. In 2023, the city received around 60 complaints, and there have been less than 20 calls made this year so far.

While there are 13 to 15 vehicles patrolling in Winnipeg at any given time, she said, the parking authority still relies heavily on public reporting.

Andrew Kohan photo

A U-Haul truck is seen parked in a bike lane late last month.

“If a cyclist says, for example, ‘Every morning I travel this path, there are vehicles parked almost every morning,’ we can also set up more routine patrols and a more concentrated effort in those areas, rather than try to cover the whole bike infrastructure throughout the city, to try to really minimize the rate of non-compliance in one or several specific areas,” she said.

The complaint system isn’t enough to hold drivers to account, argued Patty Wiens with advocacy group Bike Winnipeg, as the city’s standard 90-minute turnaround time for complaints isn’t always quick enough.

“The way it works is we call 311, and maybe by the time that the parking authority gets there, they’re still there … they are not actively seeking this,” she said.

She pointed to Toronto, where bicycle patrol officers are, at times, tasked specifically with monitoring bike lanes across the city and recently raised the fine for parking in a bike path from $60 to $200.

“Here — one, we can’t even get bike lanes, and two, we can’t get the officers to come out,” she said.

Malak Abas

Reporter

Malak Abas is a city reporter at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg’s North End, she led the campus paper at the University of Manitoba before joining the Free Press in 2020. Read more about Malak.

Every piece of reporting Malak produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.